But, what is a deficit? And, more importantly, why does it matter?

But, as is all too often the case, the devil is in the details. What counts as government revenue? What counts as government spending? If Canada Post records a loss on its worker pension plan, should that count against the federal government budget? If the government sells its shares in General Motors, should that count? Hard questions to which there is no easy answer.

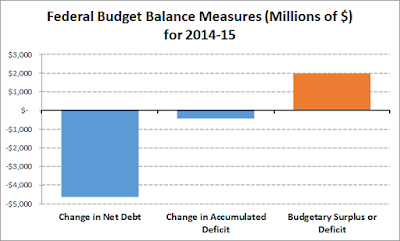

There is more than one way to measure a deficit, and the various measures sometimes tell different stories. Let's look at the 2014-15 year in particular.

Two measures show a deficit, while another shows a surplus. (For some details behind why the measures differ, see page 11 of this.) For those who like dollars:

Notice the government reports a $1.9 billion surplus, but based on change in net debt (another measure of a budget's deficit) the deficit was $4.6 billion!

First, the headline budget balance (the number everyone talks about) is what accountants would recommend (see the PSAB document). Second, there are changes in a government's "net debt". Essentially, this shows whether a government's liabilities is increasing faster than its financial assets. This measure is important economically, but also political. Remember Ralph Klein famously holding up the "Paid in Full" sign?

Alberta didn't actually eliminate is overall debt, it eliminated it's "net debt". So, changes in a government's net debt tells us how far governments are from their own Klein Moment.

The last measure I'll bring up is changes in "accumulated deficits" that also account for non-financial assets (such as physical capital). This measure is very close to changes in a business equity, but for the government.

Luckily, it really doesn't matter what measure you use most of the time. They usually tell the same story. Below I plot those three measures as a share of Canada's GDP. Notice you can barely even see differences between the lines in most years.

But they don't always agree, as the earlier bar graph demonstrated.

Let's move away from specific measures and think about whether budget balances matter in general. Is the economy harmed by deficits? The CPC and NDP seem to think so, as they both insistent budgets should always be balanced. Justin Trudeau and the Liberal party are taking the other side. They claim we need deficits to "stimulate" the economy (here or here). Are they right?

It's tricky to know for sure -- and providing clean and clear evidence on the effect of government taxes and spending on an economy requires extremely clever empirical strategies. The difficulty is, government spending is generally higher in a recession (more EI cheques, for example) and revenue is generally lower (lower income taxes). So, deficits are correlated with recessions but this doesn't mean deficits cause recessions (at least, not any more than cheese kills people in their sleep). Also, government may ramp up spending in recessions (to "stimulate" economies) and then subsequently economies start to grow. It may look like the stimulus spending helped the economy, but perhaps the economy was going to grow anyway.

Thankfully, there are clever researchers out there and they have some evidence. Interested readers can find a summary here. Most relevant for Canada, the most recent evidence suggests small countries that are open to trade and have flexible currencies (which Canada has) should expect ZERO effect of government spending on GDP. For a variety of reasons (currency movements, interest rate adjustments, consumer spending changes, and so on) the effect of government spending is likely fully crowded-out.

Does a zero effect mean we should always balance the budget each and every year? No. My colleague Ron Kneebone, in a great summary of government budgeting (here), provides a simply visual:

The CPC and NDP seem to currently favour the black line. Economists generally favour the red line. Balance the budget over the business cycle, not every year.

Don't balance the budget each year, but don't run perpetual and permanent deficits either. This consensus doesn't stem from strong evidence of stimulative effects of spending during recessions but more from sensible smoothing of program spending and tax policy over the business cycle. Keep in mind that this has nothing to do with the size of government. You can balance the budget with a higher level of taxation just as easily as with a low level.

Okay, let's review.

Was Canada's 2014-15 budget balanced? That's in the eye of the beholder. My take is simple: yes, the budget is "balanced" because inflows and outflows (however measured) are roughly the same magnitude. Imbalances on the order of tenths of a percent of GDP just don't matter -- at all. In this election, let's focus less on the binary metric of having a balanced budget or not and talk about policies and programs we do or do not favour.

Will a deficit stimulate Canada's economy? The evidence suggests stimulus probably wouldn't do much to Canada's GDP. Advocates of stimulus spending must present evidence for why they think it will help and why the existing evidence is wrong. They usually don't. We must demand better.

Nice post! Two things:

ReplyDelete- The "change in net debt" measure of budget balance will usually be below the two other measures due to growth in the nominal value of non-financial assets. Indeed, the blue line in the graph is consistently fractionally below the red line. This is not so important when looking at the federal budget, but very important when looking at provincial budgets, as provinces own much more non-financial assets. Opposition parties in balanced-budget provinces almost always complain about increasing net debt (or even gross debt), and it'd be useful for the public to understand that unless non-financial assets are increasing much faster than GDP, these complaints are dumb.

- About the stimulus, it'd probably have more of an effect in places that are up against the zero lower bound. Whether Canada, at a 0.5% rate, is feeling the effects of that bound is up for debate...

Thanks, great points. The effect that being at the ZLB has for government spending multipliers when currencies is flexible is up in the air. It's a very active area of research that I'm still digesting. (UBC's own Michael Devereux has some related work here.) But, one thing the recent crisis has shown is that monetary policy is much more about the bank rate. Forward guidance, asset purchases, etc, can all still operating despite overnight rates being stuck at zero.

ReplyDelete